by José Luis Falconi at Espacio El Dorado

Contrary to common belief, Colombia is a country without landscapes. The country might be plagued by riveting natural scenery but these have yet to be transformed into recognizable national landscapes.

In fact, if any country in Latin America has been set up against its own impressive geography, it is Colombia, as its national repertoire is riddled with tales and stories in which the impossible terrain has betrayed or stalled the nation building process since the country’s inception— if one remembers, in Issac’s Maria (1867) the indomitable natural surroundings work against the fulfillment of the lovers’ desires, while in Rivera’s La Voragine (1934), it is the wilderness of the llanos which drove the protagonist to madness.

Chief among these tales are those dedicated to the “Paso del Quindio,” an arduous but strategic overpass in the Cordillera Central of the Andes, in the route that connected Bogotá with Popayan and other main cities in the central western region of the country. With all the other possible routes connecting the two main cities of the early colonial period in Nueva Granada obstructed by snow-capped mountain ranges, the only feasible route was this trail, originally used by indigenous populations, and maintained by the Spanish conquistadores who crisscrossed the region in search of the gold of the Quimbayas.

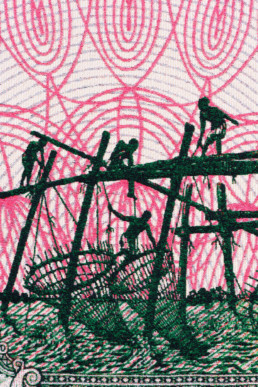

These very Spanish conquistadores were the first to make this trail legendary. As they hunted for gold they reported the treacherous mountainous terrain of the “paso,” characterized by thick “guaduales” (bamboo forests) filled with sharp spurs capable of tearing flesh and armor. Later, in the eighteenth century it was the travelers on scientific expeditions who added to the terrain’s mythology their vivid descriptions of the “cargueros” (carriers), the man-beasts capable of transporting people and cargo directly on their backs in hazardous surroundings. By the time Alexander Von Humboldt arrived to the area at the turn of nineteenth century to introduce it to the world as one of the most diverse in terms of its flora, the “Paso del Quindio” was as fabled as it was hard to overcome.

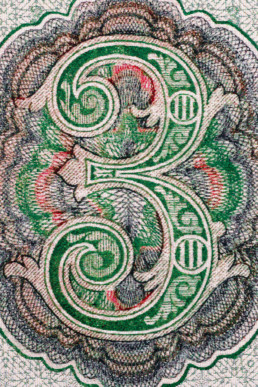

With this cumulous of fables and myths about it, “El Paso del Quindio” secured since very early on a particular place in the Colombian imagination and, for the last two hundred years has become a near perfect metaphor for the challenges and potential of the nascent republic. Located in the heart of the heart of the coffee region (which became the most important crop for decades in the country and which articulated its first agro-exporter elite), the “Paso” represents both intractability of the terrain, and the Edenic and fertile ecosystems on which Colombia has been established. In other words, the “Paso” is perhaps the most definitive image metaphor for the curse of (natural) riches with which Colombia has been dealing since its inception.

And, for all these reasons, it should not come as a surprise that it serves as the foundational metaphor for artist Santiago’s Montoya first exhibit in his native Colombia in over a decade, Malpaso (and other routes). He has not only lived for years in Armenia, but has also structured his artistic practice on the exploration of value behind monetary transactions and cash itself. In that sense, just as his previous works, this one is also an exploration into the inherent fiction behind what one might find valuable.

Displayed across the three floors of the El Dorado building, which in turn comprise three major installations, each of them reinterpreting the experience of crossing a dubious path to riches and fortune, “Mal paso (y otros senderos),”aims to make its spectator question and reflect on the shortcomings and illusions of the Colombian national project.

Choreographed as an ascension out of hardship into a state of dubious, suspect grace and fortune, the show consists of three interlocking site-specific pieces –one on each floor—which, as we said, reinterpret the crossing of the “Paso del Quindio.” In that sense, the exhibition asks from its viewer to inhabit and traverse the strange space opened by the critical distance between the dreams of wealth and prosperity and the actual reality of their very dreamers.

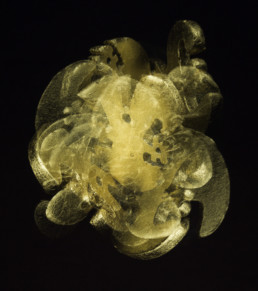

At the ground level, the spectator is first confronted with Tally Sticks (2017), an immersive, idiosyncratic penetrable sculpture of one objective correlative of the ubiquitous golden paradise in the Americas: the tropical forest that surrounds or blocks it, making it ultimately inaccessible. Created from over one thousand sticks made of “guadua”, the very same plant which made the traversing of the Paso into a colonial nightmare, a hellish undertaking. Thus, by transforming spectators into reluctant dwellers from the get go, Malpaso (y otros senderos) establishes itself as a crossing, not only thematically but also at the experiental level, as it pushes him or her into a prolonged surmounting (Tally Sticks continues the second floor) of the thick forest.

And it is precisely in this forced march between the guaduales that, on the second floor, in what appears to be a clearing between the bamboo, we stumble into— as if it were a mirage— a traditional church choir (Malpaso and other paths, 2017). The spectator would be wise to attend the type of music this choir are singing, as it contains not only the most central clue as to the type of analysis the artist has undertaken of Colombian history, but also because they add a layer to the illusory nature of the show. Suffice to say that illusory choirs might only sing (the most wholehearted) illusions.

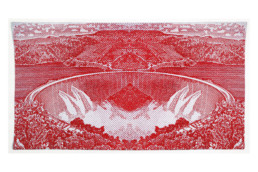

Rewarding the traveler-spectator, having emerged from “el paso,” the third floor offers, in The Original’s Inn (2017) the ultimate of tropical mirages: a comfy lounge. In it, lavishly covered with beautiful tapestries depicting exotic sceneries, and surrounded by statues made out of pure cacao (one of the most precious of America’s original crops, and one which is heavily cultivated in the Quindio region in the present) and recovered in gold powder, the tired spectator could enjoy a cup of hot organic chocolate while kicking back, relaxing and witnessing the slow melting of a collection of conspicuous icons of popular culture–and which end up composing, as a whole, the most accurate portrait of the Colombian national unconscious.